|

8 October 2007

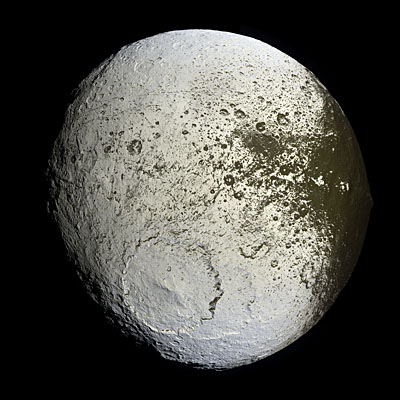

Scientists are on the trail of Iapetus' mysterious dark side, which seems to be home to a bizarre 'runaway' process that is transporting vaporised water ice from the dark areas to the white areas of the Saturnian moon.

This 'thermal segregation' model may explain many details of the moon's strange and dramatically two-toned appearance, which have been revealed in exquisite detail in images collected during Cassini’s recent close fly-by of Iapetus.

Infrared observations from the fly-by confirm that the dark material is warm enough (approximately -146°C or 127 Kelvin) for very slow release of water vapour from water ice, and this process is probably a major factor in determining the distinct brightness boundaries.

"The side of Iapetus that faces forward in its orbit around Saturn is being darkened by some mysterious process," said John Spencer, Cassini scientist with the composite infrared spectrometer team from the Southwest Research Institute, USA.

| |||

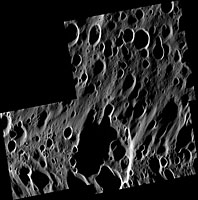

A Scene of Craters |

Scientists are now converging on the notion that the darkening process in fact began in this manner, and that thermal effects subsequently enhanced the contrast to what we see today.

"It's interesting to ponder that a more than 30 year-old idea might still help explain the brightness difference on Iapetus," said Tilmann Denk, Cassini imaging scientist at the Free University in Berlin, Germany. "Dusty material spiraling in from outer moons hits Iapetus head-on, and causes the forward-facing side of Iapetus to look slightly different than the rest of the moon," said Denk.

| |||

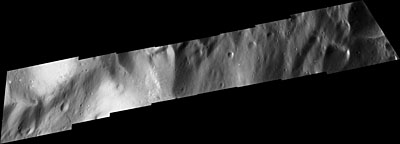

Slim crescent of Iapetus looms |

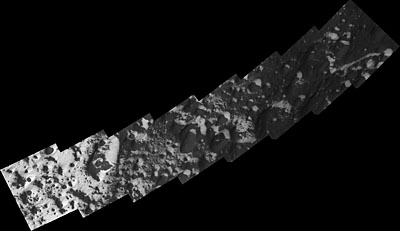

Scientists say the result is that there are virtually no shades of grey on Iapetus. There is only very black, and white. Ultraviolet data show there is also a non-ice component in the bright, white regions of Iapetus. Spectroscopic analysis will reveal whether the composition of the material on the dark hemisphere is the same as the dark material that is present within the bright terrain.

"The ultraviolet data tells us a lot about where the water ice is and where the non-water ice stuff is. At first glance, the two populations do not appear to be present in the pattern we expected, which is very interesting," said Amanda Hendrix, Cassini scientist on the ultraviolet imaging spectrograph team at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USA.

|

Because of the presence of very small craters which excavate the bright ice beneath, scientists also believe that the dark material is thin, a result consistent with previous Cassini radar results. But some local areas may be thicker. The dark material seems to lie on top of the bright region, consistent with the idea that it is a residual left behind by the sublimated water ice.

Solutions to other mysteries are coming together. There is more data on Iapetus' signature mountain ridge that gives the moon its 'walnut-like' appearance. In some places it appears subdued. One big question that remains is why it does not go all the way around. Was it partially destroyed after it formed, or did it never extend all the way around the moon? Scientists have ruled out that it is a youthful feature because it is pitted with craters, indicating it is old. And the ridge looks too solid and competent to be the result of an equatorial ring around the moon collapsing onto its surface. The ring theory cannot explain what look like tectonic structures in the new high resolution images.

Over the next few months scientists hope to learn more about Iapetus' mysteries by further analysing available data.

|

See more images from the fly-by here

Notes for editors:

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA and the Italian Space Agency.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a division of the California Institute of Technology, manages the Cassini-Huygens mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. JPL designed and assembled the Cassini orbiter. ESA developed the Huygens Titan probe, while ASI managed the development of the high-gain antenna and the other instruments of its participation. The imaging team is based at the Space Science Institute, USA.

No comments:

Post a Comment